Imagine a wadi. A dry river bed, filled with gravel, at the foot of a tower-shaped mountain. A few trees and shrubs grow between the rubble. Night has already fallen, the mountain stands black before the night sky. The full moon is bright enough to see every pebble and every thorny twig. In this wadi there sits a camp right beside a rudimentary dirt road. The camp has a large white truck, a row of cars, some tables, a circle of camping chairs around a campfire and a few scattered tents. The fire is burning, an interrupted card game lays on a boulder and from the boiling pots in the truck`s kitchen comes a smell of roasted chicken, but nobody is there.

The inhabitants of this camp are all gathered around a giant grey boulder nearby. The boulder must have fallen from the mountain centuries ago, it is a couple of meters high, has a smoothened surface and sticks deep within the wadi sediment. Gösta is explaining something. With the rock surface behind him illuminated by his headlamp, he is only a shadow. The crowd is listening, waiting. It`s clear that something is about to be revealed. But before we get to that let us travel back to Sunday morning, when we left the deserted landscape of Qarat al Kibrit. After so much empty land and geology it`s only fair to return to the cultural side of our fieldtrip, which is what we do.

The souq in Nizwa has a modern part and a traditional one. © Michaela Falkenroth

Our first stop is the souq (market) in Nizwa. Nizwa, the former capital of Oman, lies at the southern margin of the Hajar Mountains. It is an oasis town that is overlooked by the tower of its ancient fort and crossed by traditional irrigation systems, the so called aflaj (or falaj in singular). We spend some time on the souq and buy ridiculous amounts of dates, spices and souvenirs. For lunch we sit down in a nearby park, where we learn about the falaj-systems. While Nizwa still has a running falaj, there is an even better place to understand the meaning and complexity of this old technology: the mountain oasis Misfat Al Abriyen.

The date souq shows how variable this fruit can be and how deeply it is embedded in Arabic culture. © Michaela Falkenroth

When you buy a keffiyeh (traditional headscarf) the demonstration how to bind it is for free. © Michaela Falkenroth

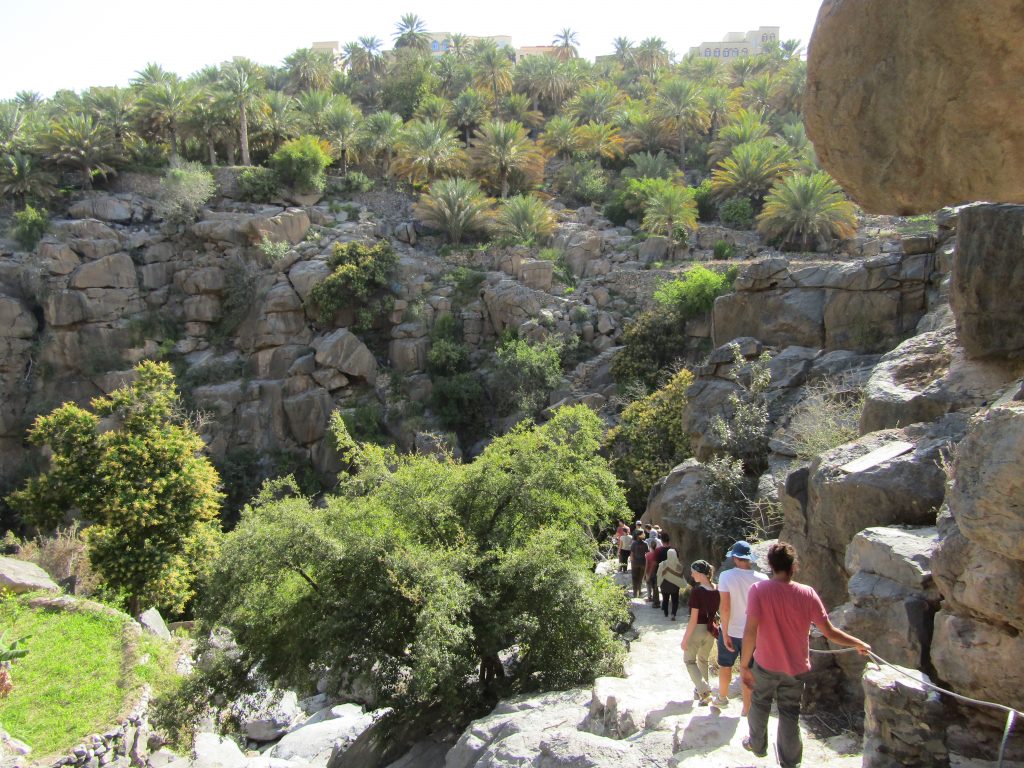

The oasis is hidden high in the Hajar Mountains and when I say ‘hidden’ I mean it. Coming from the south, the mountain looks nothing but barren. Only from higher ground you realise that there are countless oases nestled into the mountain`s rocky niches. We wander the paths of the terraced oasis, learn about the crops that are grown here and how every inch of soil is used through storey cultivation. Date palms and Mango trees are the highest level, below them grow other fruits such as pomegranates and the ground is covered in animal feed. The aflaj supplies every single terrace with water through a complex maze that is managed by a wakir (falaj master). The system works solely by gravity and usually begins at a spring or wadi. The channels are opened and closed over the day in a way that provides everyone with a fair amount of water without wasting anything. Clocks were only recently introduced to the process, before that time measurement was based on astronomy.

The oasis Misfat Al Abriyen lies well hidden between the limestone canyons of the Hajar Mountains. © Michaela Falkenroth

The falaj systems of Oman are over 1,000 years old. © Michaela Falkenroth

The oasis Misfat al Abriyen is the opposite of the desert. © Michaela Falkenroth

It`s clear that the people living in the oases are very different from the nomadic tribes that we visited in Wahiba. The people here are settled, they live in a green, lush environment and they have a constant supply of water. Obviously, they are not keen on being discovered; otherwise, they would not have hidden their oases. This spirit stayed alive until recently as obvious from the abandoned city Al Hamra, which is hidden in the same way as the villages and was inhabited until the 1970s.

The abandoned souq of al Hamra looks a lot like the one we saw in Nizwa in the morning. © Michaela Falkenroth

This brings us back to the group of people that stand around the giant grey boulder in the dark and wait for the big unveil. This boulder is located directly between the desert plains and the mountains and when you go there at night and tilt your flashlight juuuust right, the boulder stares back at you. The crowd goes: Ohhh! Ahhhh! (We call this the firework-effect.) The boulder, named Coleman`s Rock, is covered in depictions of humans, men, women and children. We have seen rock art before on this trip but these are different. They are deeply carved, life-sized and pre Islamic. One of the men raises his fists in a threatening manner in direction of the desert. Does this rock mark the border between desert nomads and mountain dwellers? Is it an ancient meeting point? Nobody knows, except for the faces in the night and they can`t tell.

The faces on Coleman`s Rock only become visible when you watch it in the right light. © Michaela Falkenroth

We stay two nights at the camp at Coleman`s Rock. There is a lot more to see in the area like the beehive tombs, which are UNESCO World Heritage or the fort in Bahla. We also get a bath in the rock pools of Wadi Dahm, which were crystal clear before and are somewhat muddy afterwards. Needless to say a bath was necessary. Rock pools might have been a bit over the top, Oman, a bucket of water would have been sufficient. But Oman replies: Egal!

The rock pools in Wadi Dahm – not the worst place to take a bath. © Michaela Falkenroth

On Tuesday, we leave the mysterious boulder behind to cross the Hajar Mountains on our way to the white wadi. See your there!

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation