At our beach camp of the last couple of days two things are very obvious. First, Gösta always makes us park in “direction of escape” and second, if you wish to avoid the toilet-tent and instead use the beach – better do it early, otherwise you risk to become amusement to the many fisherman that pass you by on their speedboats.

Fishing culture in Oman is a tale as old as time. During the Quaternary the climate of the Arabian Peninsula switches constantly between phases that were wet and warm, with high sea-levels and the formation of lakes and rivers on land, and dry and cold periods, during which wind transports sediment from the now exposed shelfs and deserts spread out. For Homo sapiens the former are a window of opportunity to migrate into otherwise inhabitable areas. But how did these early immigrants react when the rivers fell dry, plants disappeared and with them the fauna they hunted? Fortunately for them, and also for the people nowadays, below the surface of the Indian Ocean waits a second world that provides plenty of food. The shelf region of Oman is exceptionally rich in species and individuals thanks to an upwelling zone that supplies the area with nutritious deep sea water. This explains the speedboats in the morning and also why fish is on the dinner menu so often. Shortly before lunch on Friday we take a stop at the remains of many lunches some 6000 years ago. The so called shell midden is a several meter high mound of broken shells and fishbone, all animals that were consumed by our ancestors. Those people were surprisingly similar to us – already living off the sea and already throwing their packaging waste into the landscape. Fun fact: plastic bags that get caught in the spiky trees here are called ‘flowers of Oman’.

Leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). © Michaela Falkenroth

The area around Ras al Hadd, where we camp on Thursday, is not only covered in shell middens and ancient settlements, but also famous for another prehistoric inhabitant: sea turtles. During the season in August and September they come in thousands to the beaches to lay their eggs. We don`t get to see this nature spectacle, instead it comes even better. On Thursday night Achmed comes by with a basin full of newly hatched leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Apparently Homo sapiens did change since they first populated the coastline of Oman. Turtles were definitely on the snack-list of our ancestors, but as far as I can tell nobody of us thinks about a tiny turtle tart. With a strong little baby turtle in your hand the sea seems like the friendliest place.

Camels can be clingy but are not the major concern on the Omani coastline. © Michaela Falkenroth

But the Indian Ocean is both, blessing and curse for the people of Oman and this brings us back to the parking regiment. We park in direction of escape, but what are we expecting to escape from? Hint: it`s not the camels, although they can be quite affectionate, when you have food on you. No the reason is that Oman`s coastline is tsunamigenic. The true scope of this sentence falls into place when we stand on a rocky platform, 8 m above sea level and look at a 120 t (tonne) boulder that was ripped off the cliff and transported inland. So far, we know that this boulder was not moved an inch by the two strongest tropical cyclones that were ever recorded on the Omani coastline Gonu and Phet – this leaves us with another transport process: tsunami.

What kind of wave can move a boulder of this dimension? Think big! © Michaela Falkenroth

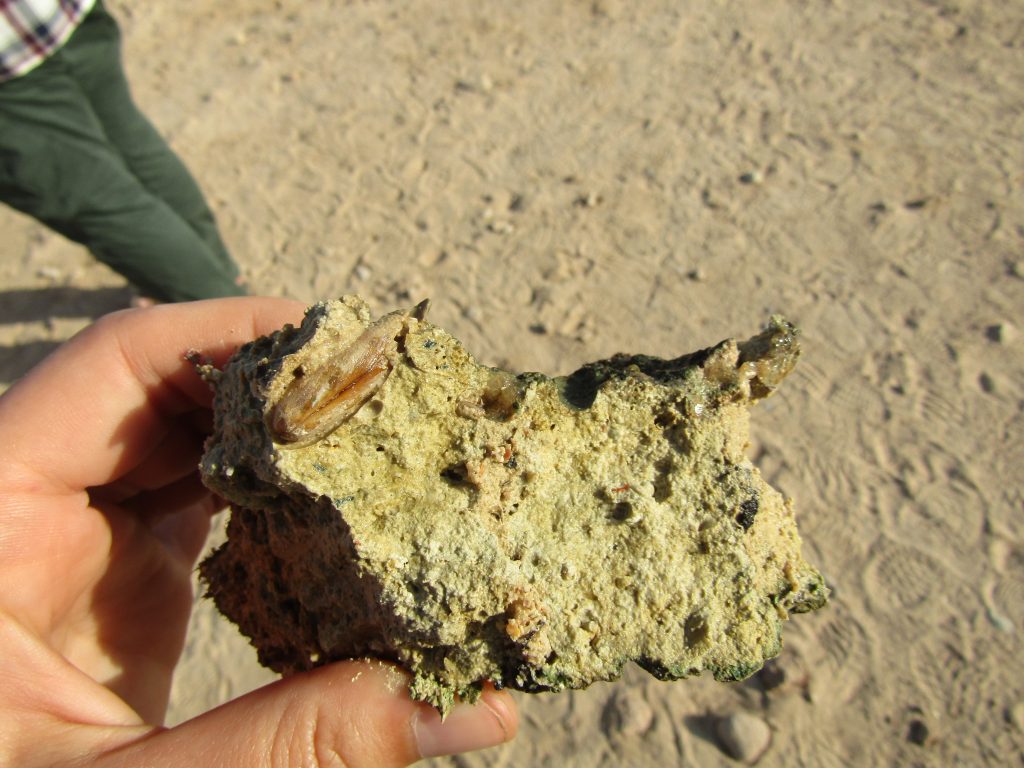

When it comes to tsunami, we always ask the same questions: how high and how often. Right now a scaled model of the boulder sits on Gösta`s desk in Bonn and waits for its turn within a wave tank to measure how strong of a wave is needed to move it. Think big! To figure out the reoccurrence interval it`s necessary to date the geological or archaeological evidence of past tsunamis. Fortunately a rock-boring clam named Lithophaga bored into many of the boulders that are found along the coast. When the boulders were thrown on land the clams died and this point in time can be dated with the radiocarbon method.

The rock-boring bivalve Lithophaga grows inside a selfmade prison that it can never leave. © Michaela Falkenroth

Apart from the boulder ridges that indicate a large tsunami some 1,000 years BP, we find other indicators from different events. In one of the bronze age settlements in Ras al Hadd a suspicious shell layer between two building phases proofs an extreme wave event that destroyed the buildings around 4,000 years BP. When you arm yourself with one or two shovels and dig into the black, smelly mud of Sur lagoon, you will find another shell layer, containing exclusively of bivalves that do not live in a lagoonal milieu. Below that shell layer it becomes even more spectacular: thick wooden mangrove stems. For all of you smarty pants who now think ‘lame – mangroves an a lagoon – what`s the big deal?’: the big deal is, that all the stems point in the same direction as if they were mowed down by one forceful event. Very likely the same event that threw all the foreign shells into the lagoon. And what lies in the direction that the stems point to? – the Makran Subduction Zone.

On the hunt for more tsunami evidence in Sur lagoon. © Michaela Falkenroth

It is known that the Makran Subduction Zone can generate large earthquakes that are a potential thread to the Omani coastline. In the aftermath of the devastating tsunami event of 2004 when early-warning systems experienced a worldwide popularity rush – Oman threw a couple of millions at a similar project. When a wave is coming Muscat will now have 30 minutes prior to landfall. However, there is no detailed plan what shall happen then. In schā’ Allāh, it will be fine.

At the end of the day it`s time for us to leave the ocean behind or maybe exchange it for a different kind of sea, a dry and sandy kind: Wahiba calls us to look at the result of the dryer climate phases. Strap in for some dune bashing in the Land Cruisers!

Ma`Salama!

No Comments

Be the first to start a conversation